Adapting Frederick Douglass’s Revolutionary Framework for Today’s Postsecondary Crisis

Frederick Douglass’s July 5th, 1852 “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?” speech offers a powerful method for examining American contradictions: systematic exposure of gaps between promise and reality, followed by moral calls for transformation. This essay applies Douglass’s rhetorical framework, not to equate contemporary barriers with the horrors of slavery, but to examine how our modern systems still fail to deliver on promises of opportunity and belonging.

~Dr. G

At 11 PM, scrolling becomes archaeology. Young people dig through job postings demanding three years of experience for “entry-level” positions, scroll past familiar texts from parents saying, “just walk in with your resume,” advice that overlooks today’s digital gatekeepers. A recent New York Times article highlighted 400,000 unfilled manufacturing jobs averaging $102,000, with signing bonuses and no college debt required. Yet for many students, especially those from working-class communities, these opportunities feel as mythical as treasure maps with no legend.

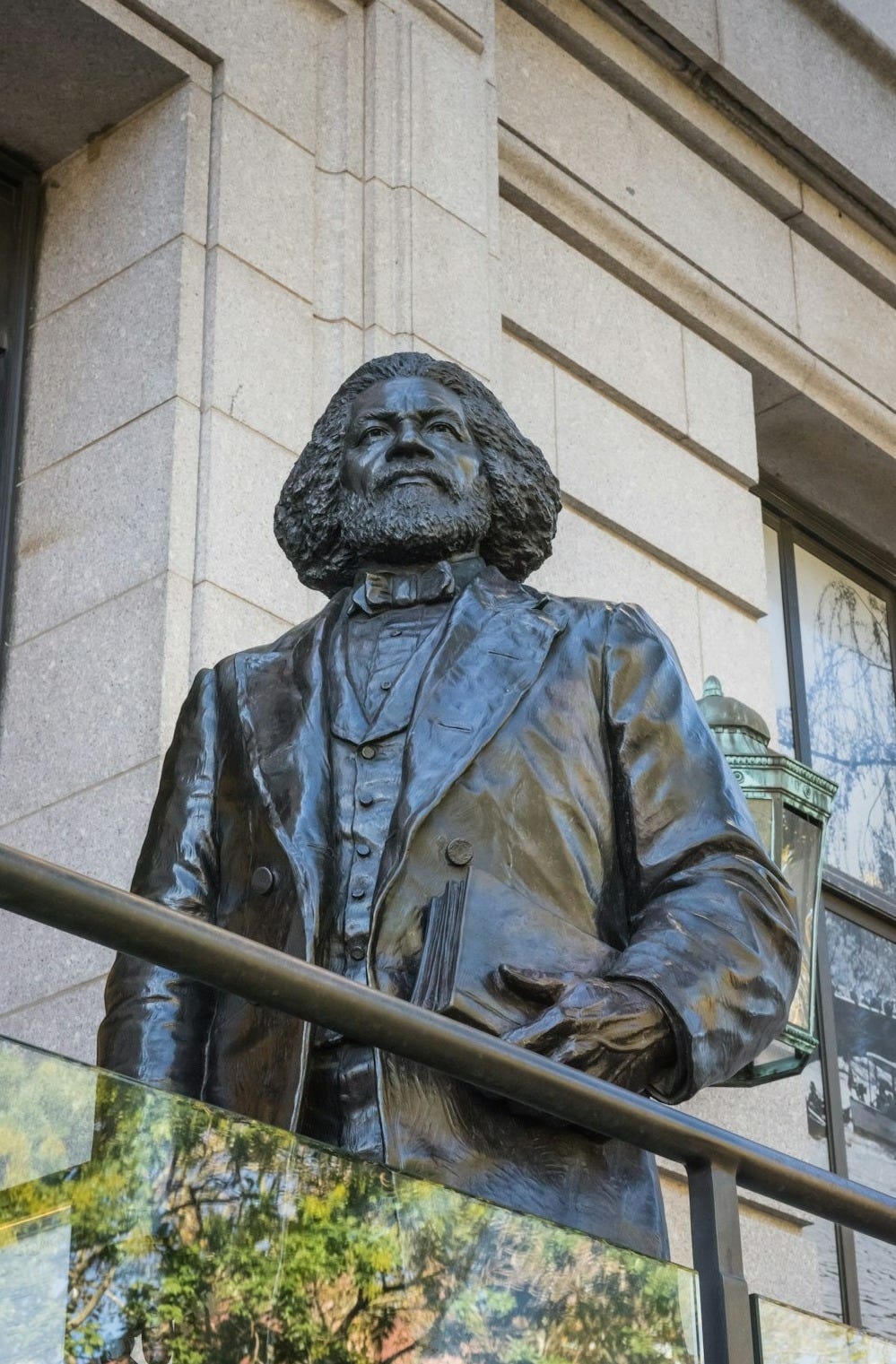

On July 5th, 1852, Frederick Douglass exposed the chasm between America’s founding ideals and its treatment of enslaved people, revealing how proclaimed values can coexist with systematic exclusion. Today, we face a parallel structural contradiction: celebrating opportunity while designing systems that make pathways invisible to those who need them most.

The contradictions multiply in both visible and subtle ways. Headlines celebrate unfilled manufacturing positions while many districts report challenges maintaining college and career counseling capacity. We celebrate the illusion of pathways, swept away by the allure of possibilities, while the human infrastructure that makes those pathways visible and accessible remains under constant pressure.

Information alone doesn’t unlock opportunity – relationships give information meaning. Students aren’t lacking data; they’re lacking the human networks that make data actionable, especially when no one in their lives has navigated these paths before. As student activist Siyana recently challenged us: “What will we create when we stop asking for permission?”

Why Systems Stay Broken: The Machinery of Disconnection

Following Douglass’s method of systematic exposure, we must trace each layer of contradiction until the pattern becomes undeniable. Like Douglass refusing to debate slavery’s moral legitimacy, we refuse to debate whether young people deserve economic security and pathways to belonging. Instead, we examine the machinery that creates systematic disconnection.

Consider Erica, the rural valedictorian whose college recommendation algorithms suggested only nearby institutions despite stellar grades. Her zip code triggered “local fit” recommendations that algorithms learned from decades of geographic sorting, creating what appears to be personalized guidance while actually perpetuating historical patterns.

When digital systems claim to expand access while encoding exclusion, they represent the technological evolution of familiar gatekeeping: more efficient, less visible, equally harmful. They don’t just reflect exclusion – they learn it. Our human experiences, shaped by centuries of inequity, become the training data for both digital algorithms and human decision-making patterns.

The cultural programming runs deeper. Manufacturing jobs paying $102,000 are portrayed in popular media as “backup plans” rather than climate innovation careers. Mainstream entertainment often portrays factory work as punishment for educational failure, while Silicon Valley narratives dominate aspirational content.

Yet today’s manufacturing involves programming autonomous systems for wind turbine production, managing AI-driven quality control in solar panel assembly, and designing sustainable materials for electric vehicle batteries. These roles require sophisticated technical skills, yet they often remain invisible in coming-of-age stories, alongside the teamwork, problem-solving, and communication skills essential for thriving in them.

Meanwhile, student-led initiatives are exploring ways to reclaim these narratives. From urban schools creating media showcasing local manufacturing innovations to rural programs connecting students with engineers who design water filtration systems and technicians who maintain renewable energy infrastructure, young people are countering Hollywood stereotypes by amplifying authentic stories about 21st-century manufacturing careers.

These outcomes aren’t accidental. Systems are designed this way – resourced unevenly, structured for sorting, and maintained by decisions that perpetuate exclusion while denying responsibility for it. When plants closed during deindustrialization, schools lost their connections to industry: relationships that once helped students see clear paths from classroom to career.

Well-intentioned “college for all” messaging made trades invisible as first-choice pathways for capable students. Counselor preparation programs shifted focus away from career pathway navigation, leaving many unable to translate between student dreams and labor market realities. When algorithmic systems entered this fractured landscape, they automated existing biases at unprecedented scale, learning from decades of disconnection and calling it smart matching.

The result? Students face what feels like constant cultural translation even at colleges that should fit their academic abilities. This exhausting reality affects first-generation students and students of color most severely. This isn’t personal failure. It’s what happens when institutions embed middle-class cultural norms as invisible requirements for success, creating belonging uncertainty that quietly chips away at confidence, connection, and mental health.

Too often, institutions avoid confronting these realities, fragile in their self-image and hesitant to ask the uncomfortable questions that would expose their gaps in serving students equitably. Meanwhile, the very counselors who might help students navigate these contradictions face resource constraints in districts across the country.

But the stakes extend beyond individual disappointment. When capable young people cannot access economic pathways, entire communities lose wealth-building opportunities across generations. When students like Erica receive algorithmic recommendations that narrow their options based on zip code rather than potential, we lose the diverse leadership needed to address climate change, technological innovation, and economic justice. The system sorts when it should connect, excludes when it should bridge.

Here’s what institutions don’t expect: communities are building around broken systems with evidence-based alternatives that challenge the very logic of sorting over belonging.

What Success Actually Looks Like

After exposing contradictions, Douglass demonstrated what justice looked like through concrete examples. We know that successful college access programs create what Jon discovered through his community-based organization: networks that provide cultural translation while honoring identity. Belonging isn’t created through programming alone. Belonging grows when students are seen, heard, and valued without judgment. Sometimes, the most powerful intervention is simply creating space where students can tell their story and not be diminished for it.

These programs create “social capital bridges” across K-12 and higher education. Jon’s mentors understood DACA status as requiring specific navigation strategies while recognizing bilingualism and cross-cultural competence as leadership assets, not barriers to overcome. Peer networks shared collective wisdom across transitions. Ongoing relationships provided support through challenges rather than one-time interventions.

The pathway plurality emerging from this research counters the false choice between college and everything else. Advanced manufacturing requires sophisticated technical skills, including programming automated systems and managing AI-driven quality control. Research suggests these roles represent economic justice (federal data indicates $102,000 average earnings with zero college debt), climate leadership, and technological integration that rivals any office job. States like New York are beginning to recognize this reality, covering tuition for community college students pursuing associate degrees in advanced manufacturing, AI, and cybersecurity, acknowledging these as high-demand pathways rather than consolation prizes.

When Arya transferred from her well-resourced university to community college, research reframes such choices as strategic moves toward environments supporting both academic growth and cultural belonging. What looks like stepping back is often a smart sidestep, allowing students to take charge of their own learning pace. Students choosing alternative pathways aren’t failing; they’re exercising network knowledge to make informed decisions, prioritizing both economic opportunity and psychological wellbeing.

Programs like AVID, Upward Bound, and community-based initiatives already demonstrate essential elements: mentorship networks providing cultural translation, peer connections, multi-year relationships, and approaches building on student strengths – elements proven to improve student outcomes.

The Constitutional Moment

The Douglass framework compels us toward transformation, toward moral fire that refuses to legitimize systems designed to exclude. Yet the solutions that follow may appear reformist. That tension is real and productive.

Perhaps the point isn’t choosing between moral fire and systemic design, but designing with fire, echoing Douglass’s moral clarity that refused to confuse order with justice. It’s not about tinkering with broken systems; it’s about rebuilding them with courage and care.

Blueprint: Relational Re-Architecture

Douglass envisioned constitutional principles creating justice if we build relational systems to support them. The examples emerging today point toward a relational blueprint already underway, one that communities have begun designing from necessity and care. Today’s infrastructure exists: every school has alumni, every college maintains networks, every workplace needs talent. We know mentorship networks create measurable improvements in both individual and community outcomes. The problem isn’t merely about material resources; it’s about relationship architecture and the courage to prioritize belonging over sorting.

Peer Ecosystem Networks would move beyond isolated mentorship moments toward connected mentoring ecosystems, where alumni, professionals, and community members form networks that surround students with sustained, identity-conscious support. What if recent graduates could serve as paid “transition mentors” through locally run initiatives supported by alumni networks and employers? Some communities are already exploring approaches that follow models demonstrated by successful community organizations. Identity-conscious pairing would recognize intersectional experiences while mentors share stories of strategic pathway choices, including narratives of manufacturing innovation that counter media stigma. Alumni associations and employers could co-fund positions with community oversight.

Cross-Sector Partnership Infrastructure would coordinate what promising programs like Year Up and CareerWise Colorado have begun to demonstrate: shared communication systems connecting K-12 counselors, college liaisons, and employer representatives. Early research highlights how wraparound integration – encompassing transportation, childcare, and flexible scheduling – can enhance completion rates and improve postsecondary transitions. Communities are exploring such coordination, adapting these models to local needs and constraints, often moving forward regardless of policy support.

Community Leadership Systems could ensure students and families shape program design, using governance structures that successful community-based access programs have tested. Community-led platforms might let students set priorities, measure outcomes, and create narrative content. This could include supporting youth-led media production that counters Hollywood stereotypes, while providing intergenerational healing resources to help parents process trauma related to deindustrialization and celebrate new opportunities.

Technology serves as scaffolding for human relationship, not replacement. Digital platforms become bridges for reciprocity, designed to foster presence and belonging. Asset-based profiles describe strengths and goals rather than focusing on deficits. Multiple pathways receive equal celebration.

Sustainability emerges through employer investment, alumni reciprocity creating circular mentoring, and research-based funding tied to long-term community outcomes rather than job placement metrics alone.

Evidence for Interdependent Transformation

Douglass’s question wasn’t just about slavery. It was about systems promising freedom while denying access. He saw the Constitution as a “Glorious Liberty Document” that could support justice if properly implemented with relational wisdom.

Our constitutional crisis mirrors his: the infrastructure exists, research proves mentorship networks work, but we lack relationship architecture with courage to center belonging over sorting. What’s emerging in communities nationwide isn’t individual success that leaves others behind, but interdependent networks where everyone’s thriving strengthens the ecosystem.

Students need to take control of their own struggles and develop their own resolution: sometimes choosing manufacturing over college debt, sometimes transferring from selective schools to find better cultural fit. These aren’t failures; they’re empowered choices requiring cultural validation and structural support.

Like Douglass’s refusal to debate slavery’s wrongness, we refuse to debate whether young people deserve pathways to economic security and cultural belonging. The question becomes: Will we build the relational and cultural infrastructure to make those pathways accessible?

This building is happening in communities nationwide. Students, educators, parents, learning engineers and technologists, employers, policymakers, and community organizers all have potential roles in this ecosystem. Start where you are. Build with who you have. Scale what research proves works. Design with fire.

This is how we bridge belonging in collaboration: with Douglass’s moral clarity applied through relational wisdom that serves transformation. The bridges we need aren’t just built from steel and concrete, or even solely from institutional policies; they’re woven from human networks that honor both individual agency and collective liberation, creating pathways where economic opportunity and cultural belonging strengthen each other rather than compete.

The scrolling can end. But will you join the building – already underway in communities like yours – that’s expanding now?